Disaster relief in an urban setting: The aftermath of Albania's largest earthquake in 30 years – Latest

In November 2019, Suzie Cooper, Structural Engineer at Elliott Wood, was deployed as part of a team of SARAID (Search and Rescue Assistance in Disaster) engineers to provide disaster response assistance to the Albanian government. We spoke to her about her experience.

What happened in Albania and what did you do out there?

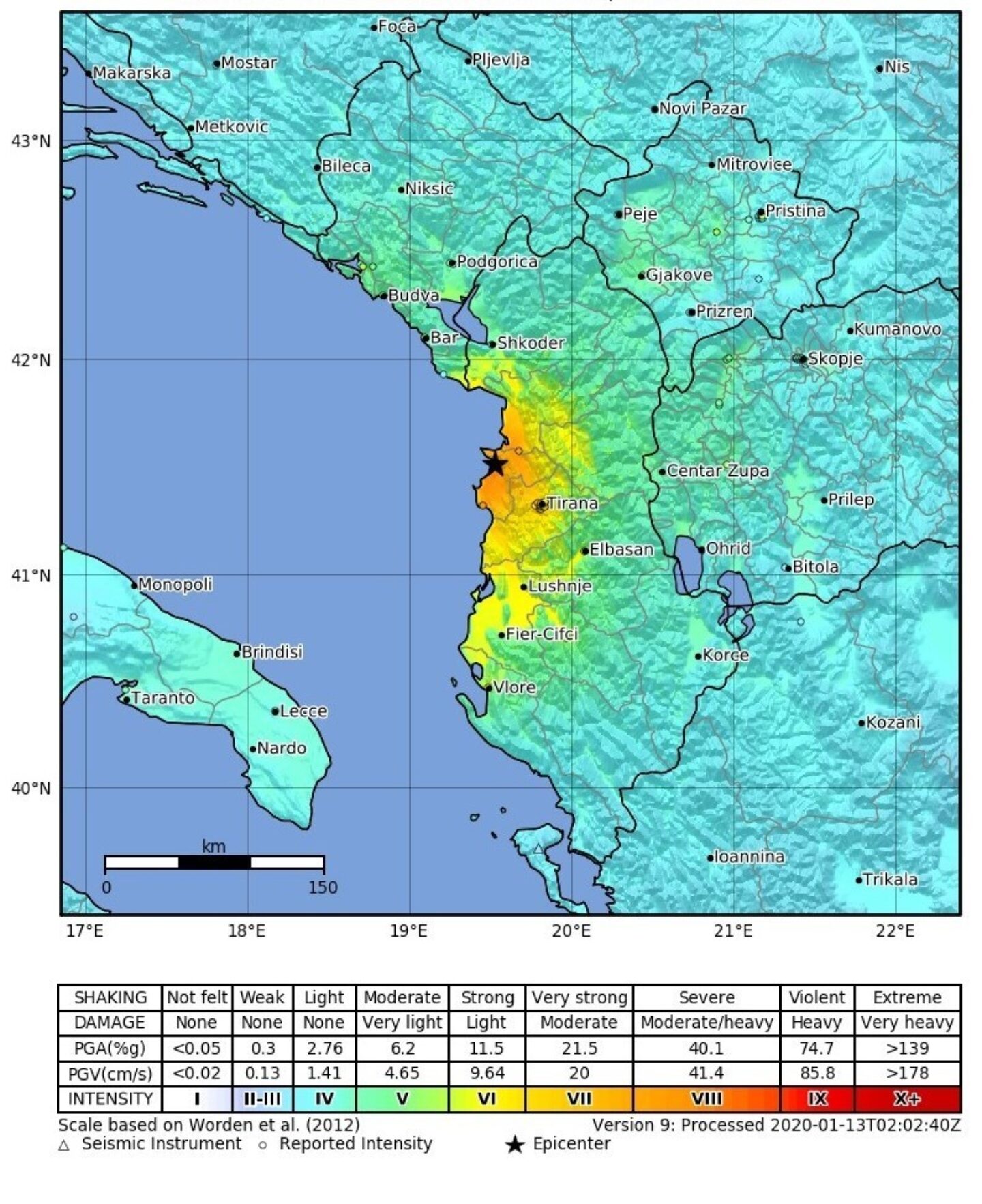

A 6.4 magnitude earthquake hit Albania in the early hours of the 26th November, causing a significant amount of damage and leaving 51 people dead.

I was deployed as part of the charity I volunteer for, SARAID, with the aim of working alongside the Albanian engineers to decide if structures were safe to be inhabited, as well as to assign a level of damage to each building. This provided the government with a better understanding of building damage and allowed them to prepare for the detailed assessments and future reconstruction.

So what does SARAID do?

SARAID are a charity who provide emergency disaster response assistance to countries in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. Specialising in USAR (Urban Search and Rescue), we search through damaged and collapsed buildings, finding survivors and pulling them to safety using a variety of technical skills, teamwork and specialist equipment. It is staffed entirely by volunteers and funded solely by public donations.

How would you describe the general condition of the infrastructure after the earthquake?

On arrival, the buildings appeared to only have superficial damage. However, once we started the assessments and were assigned to more heavily damaged parts of the city, the extent of disruption became much more evident. In these localised areas, half of the buildings had significant cracking in the external facade, with some walls having completely collapsed.

In amongst streets of mid-rise buildings, you would occasionally walk past an empty plot where a building had stood, following its complete collapse, it had since been demolished. This posed as a stark reminder of the true damage this earthquake had had. Although, even in these areas, shops, restaurants and bars were all open - life continues!

What area was your team covering and how many buildings did you assess?

SARAID deployed a team of four engineers. We split into two teams, both working with local government officials and engineers. Together we assessed over 100 buildings in the coastal city of Durres, to the west of the capital Tirana. Within the city different areas had varying degrees of damage. We spent most of our time to the south of the city working along the coastline, one of the more heavily affected areas.

What sort of things would you look out for when assessing a building’s condition?

Cracking is the most common thing, however it was the crack location that was key. Whether the crack was in a structural element or in a partition feeds into the decision of how severe the damage is. As we often didn’t know the structural form, due to it being hidden behind finishes, we would look at the cracking patterns as indicators for where the crack propagated. It’s important to note that in some cases, although the cracking was limited to only the non-structural elements, the damage to these were so severe that the building was uninhabitable due to the risk of elements falling.

Other things we looked out for were any alignment problems; is the building now leaning at all? Had there been any settlement due to the earthquake? Other notable damage was flooding in the basements and concrete crushing or spalling in the columns and beams.

Why isn’t your work being undertaken by local authorities?

It was to some extent. Each day we were sent out with an Albanian engineer to assist them with this work and provide advice in instances where they were unsure. They needed international assistance due to the sheer quanity of buildings to assess, there were not enough local engineers to be able to cover the ground required. More so, many had little experience of earthquake damage assessment as this is the first major earthquake they had experienced in their lifetime. From our training we were able to provide further understanding but also pass that onto them, so that they were able to continue this work once we had left.

There was also a large social aspect to our work. Everyone was very scared of another earthquake and whether their house will be able to withstand it. It's an impossible question to answer, however being there and discussing our work with the residents and explaining what the damage meant gave them some peace of mind. I found they took a lot of reassurance from an 'international' engineer being there providing this information, who is an outside party to the situation at hand.

What would you say are the main differences in construction between the UK and Albania? Do they consider earthquakes in design?

There were two main categories of construction in Albania, which are mainly differentiated by date. If the building was post 1990 it would typically be an RC moment frame. Waffle slabs were used extensively in these RC building which are not as common in the UK.

Pre 90s the buildings are a lot more varied, mainly consisting of load bearing masonry. Particularly in these older structures, the buildings have often been heavily modified, sometimes without any regulation. It was often difficult to see what, if any, structure was installed for these alterations and therefore it was challenging to understand what the original building looked like and what effect the alterations had had on the way the building reacted to the earthquake.

The big difference to UK construction is that I didn’t see a single steel building. Another is that partitions and facades were always made from terracotta hollow blocks, never timber. We would generally assume that in an earthquake zone a brittle material such as this should be avoided however it is everywhere. We even drove past multiple factories manufacturing them. Clearly it is a readily available material that is quick and easy to construct.

Speaking to the local engineers there are buildings codes, and these do consider earthquake design however, even now, not all buildings are designed using them. Owners and contractors still try to save a few penny’s and cut corners which is deeply saddening when you then see the catastrophic effect this can have.

What were the main failure mechanisms?

Most of the failure was in the brittle hollow block partitions and could be classed as non-structural damage. In these partitions it was common to see shear cracking in the direction of the movement, these would present as diagonal cracking in the wall.

Where there was structural damage, it was often in ground floor columns where compression failure had occurred. The concrete had crumbled, and the reinforcement bulged out. In these columns there was often a lack of and poor detailing of link bars therefore they were doing little to confine the vertical bars.

Along the seafront saw an extensive amount of damage, we were informed by many of the locals that the area used to be ‘marsh’ land. This appeared to have had a visible effect on the amount of damage to the structures as the soft ground has amplified the earthquakes movements.

What made you join SARAID?

I have always been interested in the humanitarian sector and wanted to use my skills as an engineer to help people. My manager pointed me in the direction of SARAID. I went along to an open day not really knowing what to expect and 18 months later I’m still a part of it.

As much a training can be grueling it’s nice knowing that if the worst happens to a community we are ready to help. We train for something we never wish to occur, but if it does, the highly skilled team are ready to deploy to ultimately try and save lives. That’s nice to be a part of.

It’s been such a journey this past year and I am so pleased I got involved. I’ve learnt so much about myself and have been put in situations where I’ve been really tested, which has helped me to develop loads of new skills.

How can I get involved?

Each year SARAID has an open day followed by a selection weekend which all new members must attend and pass. We highlight and replicate the sort of conditions we work in, the skills that a member is expected to learn and explain the responsibility of all members to fundraise. During the weekend new members are introduced to search and rescue techniques that they are required to perform within challenging scenarios. This is part of a tough weekend where participants will have limited sleep and are required to physically exert themselves walking around the hills of Bath. If successful, 18 months of training (training is one weekend a month) follows where members are taught all the skills they need to be a Search and Rescue technician.

More information on donating to, joining and the work SARAID do can be found here - https://www.saraid.org/

To hear more about Suzie’s deployment, join us at The Building Society at 9am on 25th Feb where she will be giving a presentation about it.

https://www.thebuildingsociety.org/en/events/view/1231821833/disaster-relief-in-urban-setting--albania-earthquake-2019