Engineering an equitable society – Latest

By Gian Cabanas, Sophie Collier and Ella Seed

2020 has brought two topics starkly into the national consciousness: health and equality. While COVID19 was a new and unexpected bombshell, the Black Lives Matter movement has focused attention on the longstanding issue of racism and inequality.

If we are to succeed in engineering a better society, an understanding of these interlinking issues must now become central to our practices and thinking in the built environment. Working together, we must champion diversity and explore how inequality and racism are perpetuated through design and in our industry. It is our responsibility to be part of the solution – to create buildings and spaces that are inclusive, safe, provide equal access and opportunities and promote the wellbeing of all our communities.

The built environment has a formative impact on the lives of individuals and can be a powerful force for good. As designers, we are able to impact the fabric of society and transform people’s quality of life.

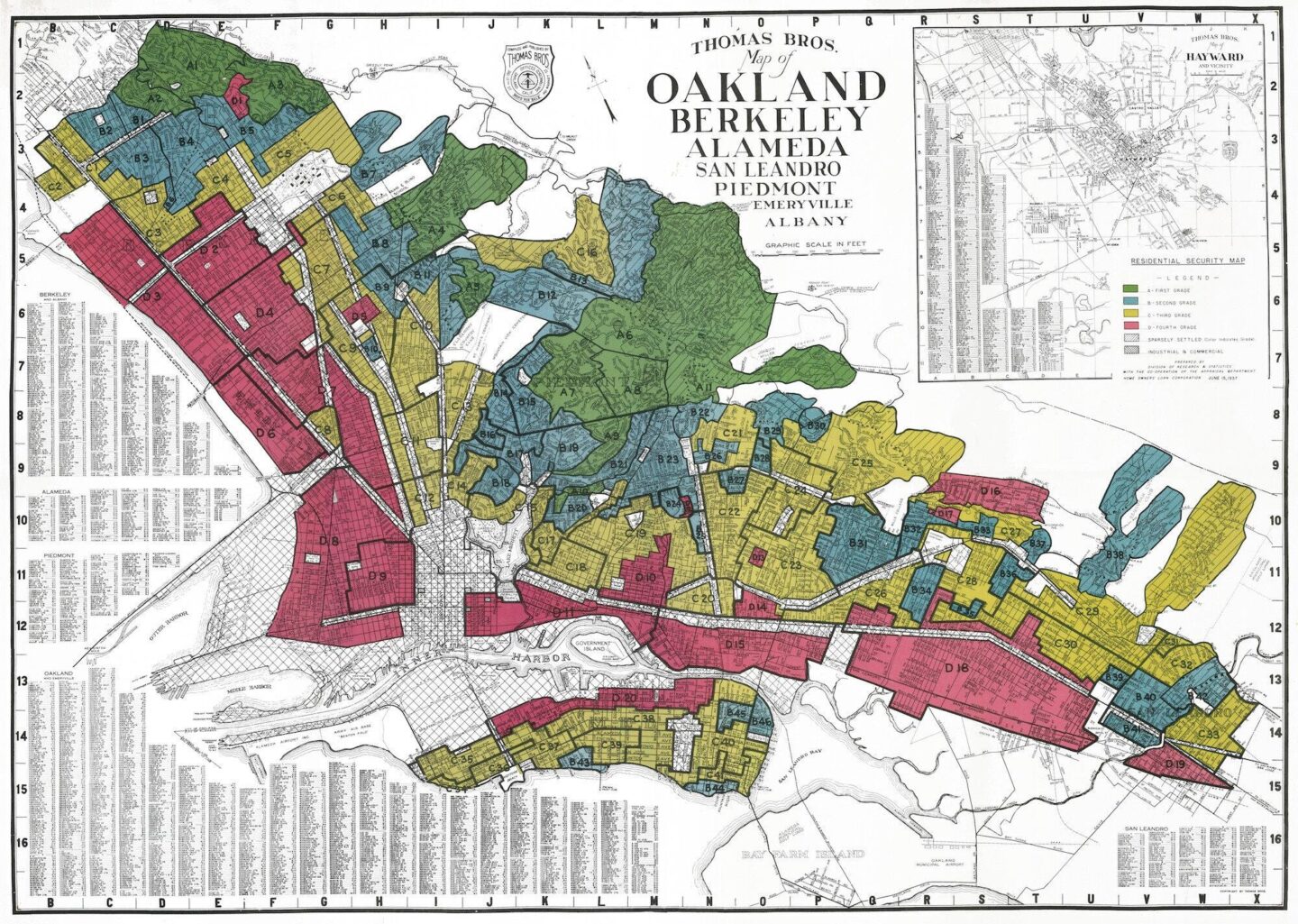

Yet urban design is also used as a tool to segregate and disadvantage minority groups. While this continues today on a more subtle basis, the overtly racist policies of the past help to demonstrate precedence.

Architecture of exclusion

In the early 1900s, as part of the transformation of New York, minority neighbourhoods were bulldozed for urban renewal, public parks and pools were specifically distanced from black communities, and 170 bridges were designed to low for buses to drive under, so that minority ethnic groups could not access de facto white beaches. The principle designer, Robert Moses, argued that that ‘legislation can be changed but it’s very hard to tear down a bridge once it’s up’. Blatant housing discrimination prevented African Americans from buying homes, and black and less affluent neighbourhoods were designated as undesirable for investment through redlining, causing systematic denial of public services to minority ethnic groups [1,2].

This architecture of exclusion was designed by built environment professionals and continued until the 1960s, leaving behind a legacy of deeply segregated cities with societal problems that we still live with. Today, black communities in America that were purposely located in undesirable areas (e.g. near highways) has led to black people being exposed to 56% more air pollution compared to their white counterparts, which translates to up to 16 fewer years in life expectancy [3]. Two thirds of black children currently live in high-poverty communities and neighbourhoods with few amenities and support structures, limited access to fresh food and green space, and entrenched obstacles to economic and social opportunities [4].

In the UK, housing continues to directly contribute to racial inequality and segregated communities. As in the historic example above, black people continue to be exposed to more air pollution and are more than four times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people [5].

Another example is the deliberate neglect of council estates that actively turns them into ‘sink estates’ to pave the way for redevelopment. This ‘managed decline’ of estates was embodied by the Grenfell Tower tragedy and in the continuing method of ‘constructive eviction’ that occurs under the guise of gentrification. BAME populations are over-represented in social housing in London, so we cannot continue talking about the regeneration of its council estates without acknowledging it as a racial issue [6].

There are many voices within and outside of the field who have been highlighting issues such as these for years. Listening and amplifying their activism is key, but collective action is needed, as we have started to see with the response to climate change. Ensuring power and decision-making doesn’t rest solely in the hands of one monolithic group is important, and there is much work to do to diversify the sector at all levels.

(Pictured right: Map of Oakland, California showing redlining)

BAME representation within the built environment

In order to ensure we are designing our cities and rural environments in ways that are beneficial to all communities, we must actively cultivate diverse design teams. At present, minority ethnic groups represent 14% of the UK population, yet account for only 1.2% of the people working in the built environment.

We know that individuals from a BAME background face significant hurdles in the industry. Research by the Royal Academy of Engineering found that even after controlling for such factors as degree attainment, employability outcomes for BME graduates were weaker than for white graduates. The study also found that these differences were greater among engineering graduates than those in other subject areas [7]. Among those employed, the Royal Academy found that black engineering graduates earned an average of £1,296 less than their white counterparts [8].

(Pictured right: The 1976 inaugural meeting of the Fellowship of Engineering (now the Royal Academy of Engineering))

Looking to the future

Diversity and equality in pay and opportunity are clearly important steps: tackling unconscious bias, promoting BAME role models, amplifying diverse voices and examining issues around access to the profession and education.

The harder challenge is to tackle the structural inequality and racism that exists in society and the sector. The Architect’s journal has published the latest findings from its investigation on race within the industry [9]. Key findings include:

- 43% of Black, African and Caribbean respondents say racism was ‘widely prevalent’, compared with 30 per cent two years ago

- Only 17% of white respondents think racism is widespread in architecture. A rise from 9% in 2018

We must speak out against racism when we encounter it. And strive to understand and challenge the structures around us that serve to perpetuate inequality and disadvantage particular groups. This is not an easy task but it is one that as a community of creative thinkers we are equipped to come together to collaborate on.

And we must look inwards. We take responsibility for the fact that as a company we have not done enough to challenge the structures and practices that reinforce inequality. We are committed to educating ourselves and changing from within, both at Elliott Wood and in collaboration with our community at The Building Society.

It is up to all of us to challenge ourselves and the industry to do better, and to engineer an equitable society.

References

- Segregated by design

- Yale Law Journal

- Greater Greater Washington

- Policy Link

- Institute of Race Relations

- The Guardian

- Royal Academy of Engineering

- Royal Academy of Engineering

- The Architect's Journal

Additional Resources

- Richard Rothstein - The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

- Akala - Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire

- Jessica Trounstine - Segregation by Design: Local Politics and Inequality in American Cities

- Douglas Massey & Nancy Denton - American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass

- Lowkey - Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain's Underclass

- Johny Pitts – Afropean: Notes from Black Europe